The Ancient Roots of the Wendigo Legend

In the frozen heart of the subarctic wilderness, a chilling shadow has haunted the forests for centuries. The Wendigo legend origins can be traced back to the oral traditions of the Algonquian-speaking peoples, long before European explorers ever set foot on the continent. From the Great Lakes to the snowy reaches of Alberta, the Anishinaabe and Cree shared stories of a creature born from the darkest depths of winter. It was more than just a ghost story, it was a warning about the thin line between survival and madness.

This ancient entity is often described as a towering, skeletal giant with skin pulled tight over its bones and a scent like rotting leaves. It is said to be a spirit of insatiable hunger that grows larger with every meal, yet it remains perpetually starving. Whether viewed as a literal monster or a symbolic representation of greed, the legend taps into a deep human fear of losing one’s soul to the wild. The mystery lies in whether the Wendigo is merely a metaphor for the harsh northern winters or something far more tangible lurking in the pines.

Key Takeaways

- The Wendigo legend serves as a vital cultural safeguard for Algonquian-speaking peoples, using the threat of a malevolent spirit to enforce social cooperation and discourage individual greed during life-threatening winters.

- The creature’s physical appearance—a skeletal, perpetually starving giant—acts as a vivid metaphor for the destructive nature of insatiable consumption and the loss of human morality.

- Wendigo Psychosis represents a documented historical phenomenon where extreme isolation and famine led individuals to believe they were transforming into monsters, bridging the gap between spiritual folklore and clinical psychology.

- The legend functions as a timeless critique of selfishness, warning that prioritizing personal gain over the well-being of the community leads to a spiritual and psychological rot that is ultimately self-destructive.

Algonquian Roots and the Winter Spirit

The Wendigo legend traces its roots back centuries to the oral traditions of the Algonquian-speaking peoples living in the harsh subarctic regions of North America. Long before European settlers arrived, these Indigenous communities shared stories of a malevolent spirit known as the wi-nteko-wa that haunted the frozen forests. This creature served as a terrifying personification of the brutal winter months when food was scarce and survival felt nearly impossible. By naming this darkness, the elders taught their people about the dangers of isolation and the spiritual rot that could occur during times of extreme famine. These stories were passed down through generations, serving as both a cultural history and a grim warning about the fragile nature of human morality in the wild.

Physical descriptions of the Wendigo often reflect the very essence of starvation and winter decay. According to traditional accounts, the creature appears as a gaunt, emaciated giant with ashen skin stretched tightly over its bones and glowing, sunken eyes. It is said to give off the pungent odor of rotting flesh, wandering the Great Lakes area and northern Canada in a state of perpetual, agonizing hunger. Despite its massive size, which grows larger with every victim it consumes, the beast remains thin because its appetite can never be satisfied. This imagery captures the concept of insatiable greed, showing how the spirit of the winter can transform a person into a monster of pure gluttony.

Many scholars and historians note that the Wendigo was more than just a campfire story, it was a psychological framework for understanding human behavior. The legend suggests that a person could be possessed by the spirit through dreams or by succumbing to the temptation of cannibalism during a desperate winter. This transformation acted as a powerful social taboo that helped maintain communal harmony and discouraged individual selfishness in a survival situation. While modern science might look for natural explanations, the cultural significance of the Wendigo remains a testament to the deep connection between the land and the spirits the Algonquian people believed resided there. What do you think prompted these ancient communities to create such a specific and haunting symbol for their winter struggles?

Anatomy of a Starving Giant

The physical appearance of the Wendigo serves as a haunting reflection of the harsh winters faced by the Algonquian peoples. These oral traditions, shared by the Anishinaabe and Cree, describe a creature that is the very definition of a starving giant. Standing up to fifteen feet tall, its frame is painfully emaciated, with ashen skin stretched so tightly over its bones that it resembles a living skeleton. This gaunt figure is said to give off the unsettling scent of rotting flesh, signaling its presence long before it is seen. Its sunken eyes glow with an eerie light, representing a soul consumed by an eternal, icy hunger.

Every physical detail of the monster highlights the toll of extreme deprivation and the dangers of the subarctic wilderness in the deep woods of Canada and the Great Lakes. According to historical accounts documented by researchers of Indigenous folklore, the creature actually grows in size every time it consumes a victim. Paradoxically, this growth never provides a sense of fullness or satisfaction. Instead, the giant remains perpetually thin and starving, serving as a powerful symbol for the destructive nature of greed and gluttony.

While modern skeptics might view these descriptions as mere metaphors for winter survival, the consistency of the reports across different tribes suggests a deeper cultural truth. The physical transformation into a Wendigo was often feared as a literal possibility for those who succumbed to the darker impulses of the human spirit. Its glowing eyes and tattered skin act as a grim warning about what happens when the balance between nature and humanity is broken. Could such a physical manifestation of hunger truly exist in the remote corners of the northern forests, or is the monster a reflection of our own internal shadows? We want to hear your thoughts on whether these traits represent a real biological mystery or a psychological cautionary tale.

Cultural Warnings Against Greed and Isolation

The Wendigo legend served as a powerful cultural safeguard for the Algonquian-speaking peoples, such as the Cree and Anishinaabe, to ensure survival during the brutal subarctic winters. In these regions, the extreme cold and scarcity of food meant that the survival of the group depended entirely on cooperation and the sharing of limited resources. By characterizing the Wendigo as a monster born from selfishness, Indigenous elders taught that putting one’s own desires above the community was a form of spiritual sickness. This oral tradition acted as a strict moral code, warning that those who hoarded food or abandoned their kin risked losing their humanity. The creature represented the ultimate taboo, reminding everyone that isolation was a death sentence in the frozen wilderness.

Beyond the physical threat of starvation, the legend addressed the deep psychological fears of being cut off from society. When a person became obsessed with their own hunger or greed, they were said to be falling under the influence of the Wendigo spirit. Historical accounts from anthropologists and Indigenous historians suggest that this belief helped prevent the breakdown of social order during times of extreme famine. By framing cannibalism and greed as a monstrous transformation, the community could identify and address anti-social behavior before it tore the tribe apart. The story turned a desperate struggle for calories into a test of character and spiritual strength.

The physical appearance of the Wendigo further reinforced these lessons through a vivid and terrifying visual metaphor. Descriptions of the creature often highlight its emaciated frame and its inability to ever feel full, no matter how much it consumes. This insatiable hunger served as a warning against the dangers of gluttony and the pursuit of excess at the expense of others. Even today, many scholars view the legend as a critique of any system that encourages taking more than one needs. It remains a haunting reminder that true survival is found in the warmth of the community rather than the cold pursuit of individual gain. Much like Appalachian folklore, these stories often use the landscape and its hidden inhabitants to explain the unexplainable and enforce cultural values.

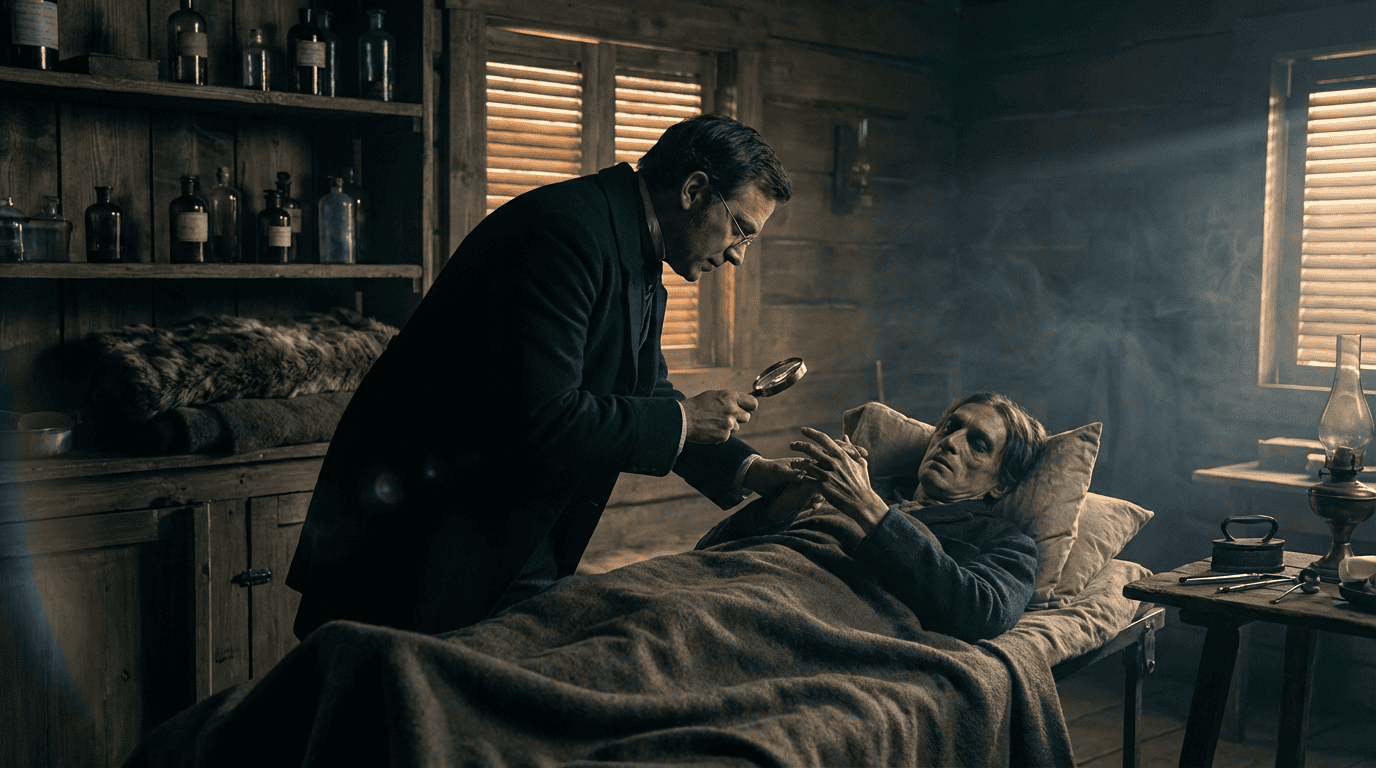

Historical Accounts and the Wendigo Psychosis

Early European explorers and fur traders often returned from the frozen wilderness with bone chilling stories about a madness that seemed to grip the northern woods. These settlers documented cases where individuals, driven by the isolation of harsh winters and the threat of starvation, claimed to be possessed by a malevolent spirit. According to historical records from the Jesuit Relations, missionaries observed that some people displayed an inexplicable craving for human flesh even when other food sources were potentially available. These accounts suggest that the Wendigo was not just a campfire story, but a lived reality that terrified both Indigenous communities and newcomers alike. The sheer consistency of these reports across different centuries and regions points toward a phenomenon that was deeply rooted in the physical and spiritual history of the Great Lakes.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, psychologists began to study these occurrences under the label of Wendigo Psychosis. This diagnosis described a condition where a person would become convinced they were transforming into a monster with an insatiable hunger. Medical professionals like John Parker have examined how the extreme stress of survival in subarctic climates could lead to a total mental breakdown. While some modern scholars view this as a culture bound syndrome, others wonder if there is a deeper, unexplained element that science cannot quite capture. The transition from a spiritual warning to a clinical study shows how society has struggled to categorize a fear that feels both ancient and deeply personal. Much like The Dancing Plague of 1518, these historical events highlight how mass psychogenic illness can manifest in response to extreme environmental and social pressures.

These historical accounts leave us with a fascinating puzzle about the line between the mind and the supernatural. If this psychosis was merely a result of starvation, it is curious why it took such a specific, monstrous form across so many different groups. Much like the Legends of the Southwest, these stories often involve humans losing their humanity to become something predatory. We have to ask ourselves if these early witnesses were seeing a simple mental health crisis or something far more mysterious lurking in the shadows of the forest. The documentation provides a bridge between the legends of the past and the scientific curiosity of the present day. What do you think caused these historical transformations, and could there be a grain of truth in the old stories that science hasn’t fully explained yet?

The Spirit of Greed and Survival

The Wendigo legend remains one of the most chilling legacies of the northern wilderness, surviving through centuries of oral tradition. While its physical form is described as a skeletal giant with a heart of ice, its true power lies in what it represents about the human condition. For the Anishinaabe and Cree peoples, the monster served as a grim warning against the dangers of selfishness and the destruction of the community. Even in our modern world, the spirit of the Wendigo feels remarkably relevant as a metaphor for corporate greed and the endless consumption of natural resources. This ancient story reminds us that some hungers can never be satisfied, no matter how much we take from the world around us.

History tells us that many communities took these stories as literal warnings to guard against a very real spiritual possession. Documented cases of Wendigo psychosis suggest that the line between a terrifying myth and a psychological reality is often thinner than we might expect. Whether the creature is a physical beast stalking the snowy woods or a dark shadow hiding within the human mind, its influence is undeniable. The legend continues to haunt the Great Lakes and the subarctic forests, bridging the gap between historical caution and modern folklore. It forces us to look at the darkness within ourselves and wonder what might happen if we let our own desires grow out of control. Similar to Australia’s mysterious swamp dweller, the Wendigo uses the natural landscape to personify the fears and values of the people who live there.

As we look back at the origins of this haunting figure, we are left to wonder about the true nature of the beast. Is the Wendigo simply a clever teaching tool used to encourage cooperation and survival during harsh winters? Or is there something more ancient and tangible waiting in the frozen shadows of the northern United States and Canada? The persistence of these sightings and stories suggests that the mystery is far from solved. Much like the modern science used to investigate other paranormal hotspots, researchers continue to look for logical explanations for these sightings. We invite you to share your thoughts on whether this legend is purely symbolic of human greed or if something supernatural truly roams the wilderness.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Where did the Wendigo legend first begin?

The legend originated centuries ago within the oral traditions of the Algonquian speaking peoples, specifically the Anishinaabe and Cree. These stories were shared long before European contact, stretching across the frozen subarctic regions from the Great Lakes to Alberta.

2. What does a Wendigo actually look like?

Traditional accounts describe a towering, skeletal giant with skin pulled so tight that its bones threaten to poke through. It often carries a scent of decay and rotting leaves, appearing as a physical embodiment of starvation and the harsh winter wilderness.

3. Is the Wendigo a ghost or a physical monster?

The creature is often viewed as a malevolent spirit that can take a physical form or possess a human soul. While some see it as a literal beast lurking in the pines, others interpret it as a terrifying personification of greed and the madness brought on by extreme hunger.

4. Why did Indigenous elders tell stories about this creature?

These stories served as a grim cultural warning about the dangers of isolation and the spiritual rot that could happen during times of famine. By naming the darkness, the elders taught their community about the importance of cooperation and the fragile nature of morality when survival is at stake.

5. Does the Wendigo ever stop being hungry?

A terrifying aspect of this entity is its insatiable hunger that only grows more intense. Every time the creature eats, it grows larger in size, meaning it can never be satisfied and remains perpetually starving despite its size and strength.

6. Is there a connection between the Wendigo and the winter season?

The legend is deeply tied to the brutal northern winters and the scarcity of food. It acts as a symbol for the thin line between survival and madness, representing the very real fears that ancient people faced during the darkest months of the year.