Beyond the Myth: The Hunt for Evidence of Atlantis

The legend of the lost city of Atlantis begins with two of Plato’s dialogues, the Timaeus and Critias, written around 360 BCE. In these texts, the Greek philosopher described a magnificent island nation located “beyond the Pillars of Hercules,” known today as the Strait of Gibraltar. This advanced civilization was said to be larger than Libya and Asia combined, possessing incredible wealth and military might. After a failed attempt to invade Athens, the gods turned against the Atlanteans, and in a single day and night of violent earthquakes and floods, the island was swallowed by the sea.

Plato’s dramatic tale has captivated explorers, historians, and dreamers for centuries, fueling one of history’s most compelling mysteries. The central question remains: was Atlantis a real place tragically wiped from the map, or was it a sophisticated allegory created to warn against hubris and imperial ambition? This enigma has inspired countless expeditions and endless speculation, challenging us to sift through ancient texts and geological data. The quest to separate fact from fiction explores the fine line between myth and a potentially forgotten chapter of human history.

Key Takeaways

-

The entire legend of the lost city of Atlantis originates exclusively from two of Plato’s dialogues, the Timaeus and Critias, written around 360 BCE.

-

The central debate is whether Atlantis was a real, advanced civilization destroyed by a cataclysm, or a philosophical allegory created by Plato to warn against the dangers of hubris and imperial ambition.

-

The most compelling scientific theory links the Atlantis myth to the real-world volcanic eruption of Thera (modern Santorini) around 1600 BCE, which devastated the advanced Minoan civilization.

-

Despite numerous modern theories and searches in locations like the Bahamas and Spain, no definitive physical evidence of Atlantis has ever been found.

-

The prevailing academic view is that Atlantis is a fictional cautionary tale, a sophisticated allegory Plato invented to explore political and moral themes.

-

According to Plato’s account, Atlantis was a powerful island nation located “beyond the Pillars of Hercules” that was swallowed by the sea in a single day as divine punishment for its arrogance.

Plato’s Original Blueprint

All knowledge of Atlantis comes from two ancient sources: the dialogues of the Greek philosopher Plato, written around 360 BCE. In Timaeus and Critias, Plato presents the story not as his own invention, but as a historical account passed down from the Athenian lawgiver Solon, who supposedly heard it from Egyptian priests. According to this narrative, Atlantis was a mighty naval power on an island “larger than Libya and Asia combined” (Plato, Timaeus). This legendary kingdom was located just beyond the “Pillars of Hercules,” the ancient name for the Strait of Gibraltar, placing it in the Atlantic Ocean.

Plato painted a vivid picture of an advanced and prosperous civilization, a marvel of engineering and wealth. The capital city was a masterpiece of design, with concentric rings of land and water connected by massive canals and bridges. Its temples were adorned with precious metals, including a mysterious, gleaming red metal called “orichalcum,” second only to gold in value (Plato, Critias). This utopian society, however, eventually grew corrupt and filled with hubris, launching an unprovoked war against Athens. As divine punishment for their arrogance, a cataclysm of “violent earthquakes and floods” struck the island, causing it to sink beneath the sea “in a single day and night of misfortune.”

Whether Plato intended his detailed account as literal history or a philosophical allegory remains a central question. Many scholars, including his student Aristotle, dismissed the story as an invention designed to illustrate a political or moral point. In this view, Atlantis serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of imperial overreach, contrasted with an idealized ancient Athens. Yet, the specificity of the geography, engineering, and chronology has led many others to believe Plato was recounting a genuine historical catastrophe, perhaps a folk memory of a real event that inspired his narrative.

An Echo of a Real Catastrophe

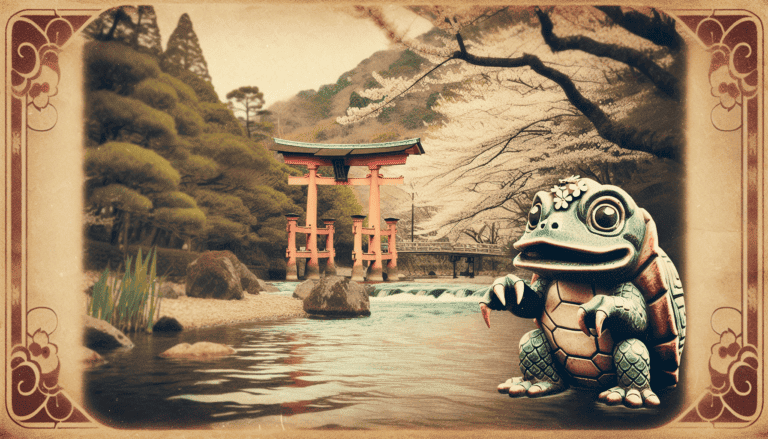

The most compelling scientific explanation for the Atlantis legend points not to a lost continent but to a real cataclysm in the Aegean Sea. Around 1600 BCE, the island of Thera, now Santorini, experienced one of the largest volcanic eruptions in human history, an event that obliterated the island’s center and triggered devastating tsunamis. This catastrophe coincided with the decline of the sophisticated Minoan civilization, a powerful maritime culture based on the nearby island of Crete. This parallel offers a tantalizing possibility: the story of a mighty island kingdom vanishing in a single day could be an echo of the Minoan collapse, passed down through generations.

Archaeological evidence from Santorini provides a compelling picture that aligns with parts of Plato’s narrative. The excavation at Akrotiri, a Minoan port city buried in volcanic ash, reveals a highly advanced society with multi-story buildings, intricate plumbing, and vibrant frescoes depicting a thriving culture. The eruption caused the island’s center to collapse into the sea, forming a massive underwater caldera that mirrors the description of Atlantis sinking beneath the waves. Geological models confirm the eruption would have generated colossal tsunamis capable of wiping out coastal cities and crippling the Minoan fleet, a key source of their power (National Geographic).

Despite these striking similarities, the Minoan hypothesis has inconsistencies. Plato explicitly placed Atlantis “beyond the Pillars of Hercules” (the Strait of Gibraltar), whereas Thera is located in the Aegean Sea, and the timeline he gives is thousands of years off from the Thera eruption. Some scholars propose a simple translation error, suggesting Plato’s Egyptian source meant 900 years instead of 9,000, which would align the timelines almost perfectly. While not a literal match, the Thera event provides a powerful, tangible disaster whose memory could have evolved into the grand legend of Atlantis.

A Map of Modern Theories

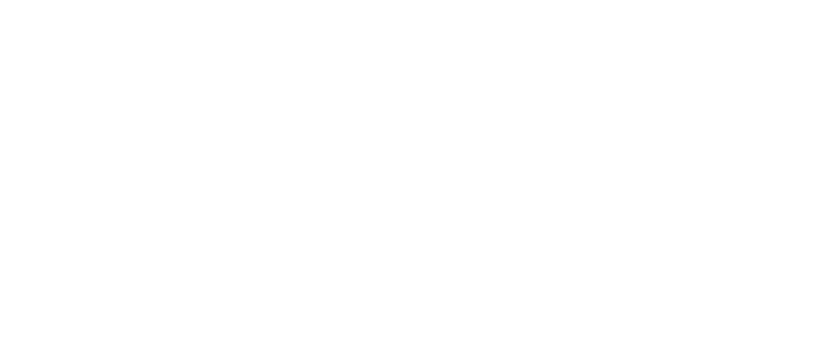

Modern searches for Atlantis have led to some intriguing, if controversial, discoveries. Perhaps the most famous is the Bimini Road, an underwater rock formation off the coast of the Bahamas discovered in 1968. Proponents argue that its large, rectangular limestone blocks appear too perfectly arranged to be natural, suggesting they are the remnants of an ancient harbor or wall. Geologists, however, have extensively studied the formation and concluded it is a natural phenomenon known as beachrock, where sediments cement together in the tidal zone. Despite this scientific consensus, the debate continues to fuel the imaginations of explorers and enthusiasts.

Another compelling theory places the lost city in southern Spain, near the Doñana National Park. Using satellite imagery, researchers have identified formations beneath the marshlands that resemble the concentric rings of Atlantis’s capital described by Plato. This region was once a vast inland sea and home to the wealthy ancient civilization of Tartessos, which mysteriously vanished around the 6th century BCE. Geological evidence of ancient mega-tsunamis in the area provides a plausible explanation for such a society’s sudden disappearance, mirroring the cataclysm that supposedly sank Atlantis. While tantalizing, no definitive ruins have been excavated to confirm the site is anything more than a natural feature.

The search for Atlantis has even ventured to the most remote corners of the globe, including Antarctica. This fringe theory, popularized by the work of Charles Hapgood, speculates that a sudden pole shift rapidly froze a once-temperate Atlantean civilization located there. However, geological evidence does not support such a rapid crustal displacement, and ice core samples show Antarctica has been frozen for millions of years. From the Mediterranean depths near Santorini to the Irish coast, each proposed location offers a unique blend of questionable evidence and compelling narrative, demonstrating how deeply the legend has captured the human imagination.

A Philosopher’s Cautionary Tale

The prevailing academic view regards the story of Atlantis not as history, but as a sophisticated allegory crafted by Plato. In his dialogues Timaeus and Critias, the philosopher presents a fictional narrative to explore themes of power, corruption, and the ideal state. He masterfully contrasts the arrogant, imperialistic sea power of Atlantis with a virtuous, land-based ancient Athens. This literary device allowed Plato to critique the political ambitions of his own society through a compelling fable, with many scholars believing the account is a thought experiment designed to teach a philosophical lesson (wikipedia.org).

The tale of Atlantis is a powerful warning against the dangers of hubris. Plato describes the Atlanteans as a once-noble people who descended into greed, avarice, and a lust for conquest. Their subsequent downfall, a cataclysm where the island is swallowed by the sea in “a single day and night of misfortune,” serves as a stark moral lesson. This narrative of divine punishment for human arrogance fits perfectly within the tradition of Greek mythology and philosophy. By creating this powerful metaphor, Plato cautioned his contemporaries about the inevitable decay that follows when a society loses its virtue and overreaches its power.

Conclusion

The quest for Atlantis, from Plato’s dialogues to modern satellite imaging, has yielded no definitive proof of the lost city. Despite countless expeditions and compelling theories connecting the legend to locations like Santorini or the Azores, physical evidence remains tantalizingly out of reach. The scientific consensus categorizes Plato’s account as a philosophical allegory: a cautionary tale about the hubris of an ideal society. This reveals a fascinating split between academic interpretation and popular belief, as every proposed location has failed to withstand rigorous scrutiny.

Yet, the absence of concrete evidence does little to diminish the legend’s powerful hold on our collective imagination. The story of Atlantis endures not because of what has been found, but because of what it represents: the possibility of a lost, advanced civilization and the profound thrill of the unknown. It fuels a spirit of adventure and encourages us to question the accepted boundaries of history and archaeology. The legend’s true power may lie in its ability to spark curiosity, pushing explorers and dreamers to look just beyond the horizon for what might have been.

The search for Atlantis reflects our own desire to believe in something magnificent hidden just beneath the surface of our world. Whether viewed as a historical puzzle, a brilliant piece of fiction, or a genuine lost chapter of human history, its legacy is undeniable. The debate is far from over, as new theories continue to emerge with evolving technology and our understanding of the ancient world. What do you believe is the truth behind the enduring mystery of Atlantis?

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Where does the story of Atlantis come from?

The legend of Atlantis comes exclusively from two of Plato’s dialogues, the Timaeus and Critias, written around 360 BCE. These ancient texts are the sole primary sources describing the lost island nation.

2. Did Plato claim Atlantis was a real place?

Plato presents the story as a genuine historical account passed down through generations from Egyptian priests. He frames it as a factual narrative of a real kingdom, not as his own invention.

3. According to the original story, where was Atlantis located?

The dialogues place Atlantis on a massive island “beyond the Pillars of Hercules,” the ancient name for the Strait of Gibraltar. This location puts the legendary kingdom in the Atlantic Ocean.

4. What is the primary evidence for Atlantis’s existence?

The only direct evidence for Atlantis is Plato’s detailed descriptions in his writings. All modern searches and theories are interpretations of his account, as no other ancient texts mention the island.

5. Why do many scholars believe Atlantis is a myth?

Many historians argue Atlantis was a sophisticated allegory Plato created as a cautionary tale. They believe he invented the powerful, hubristic nation to warn against imperial ambition and moral decay.

6. What caused the destruction of Atlantis?

According to Plato’s narrative, after a failed invasion of Athens, the gods turned against the Atlanteans for their hubris. The island was then destroyed in “a single day and night” by violent earthquakes and floods, causing it to be swallowed by the sea.