15 Mandela Effect Examples That Will Make You Question Reality

The Mandela Effect describes a situation where a large group of people shares a distinct but false memory of a past event or detail. Paranormal researcher Fiona Broome coined the term in 2009 after discovering many people, like herself, vividly recalled Nelson Mandela dying in prison during the 1980s. The South African leader was actually released from prison in 1990 and lived until 2013. The widespread nature of this specific, incorrect memory gave the phenomenon its name. This collective misremembering is the foundation for many other examples that have since been identified.

Mandela Effect examples are common, especially within pop culture. Many people are certain the Monopoly Man, Rich Uncle Pennybags, wears a monocle, but he has never been depicted with one. In The Wizard of Oz, audiences often quote the Wicked Witch shouting, “Fly, my pretties, fly!” when her actual line is a simpler “fly, fly, fly.” Iconic music videos are also subject to this effect; Britney Spears is widely remembered wearing a plaid skirt and a headset in …Baby One More Time, but she wore a plain black skirt and no headset. These discrepancies are so widely believed that the correct versions can feel jarringly wrong.

Key Takeaways

- The Mandela Effect is a phenomenon where a large group of people shares a specific, provably false memory of a past event, named after the widespread false memory of Nelson Mandela dying in prison in the 1980s.

- Common examples are found in pop culture, such as people incorrectly remembering the Monopoly Man with a monocle, Pikachu with a black-tipped tail, or the Wicked Witch saying, “Fly, my pretties, fly!”

- The effect is not just about forgetting; it is characterized by a large group remembering the exact same incorrect detail, making the correct version feel wrong.

- Psychological explanations suggest our brains reconstruct memories, not record them, leading to confabulation (filling in gaps) and errors based on pre-existing mental shortcuts or schemas.

- Individual false memories become a collective phenomenon through social reinforcement, where the internet and social sharing can create an echo chamber that validates and spreads the inaccuracy.

- The phenomenon highlights the fallibility of human memory, showing that our perception of the past is more malleable and subjective than we often believe.

Pop Culture Characters You Remember Wrong

The Monopoly Man, Rich Uncle Pennybags, is often imagined with a top hat, a cane, and a sophisticated monocle. Despite this widespread mental image, he has never officially been depicted with a monocle in the game’s history. This collective misremembering is a clear example of the Mandela Effect in branding. Many Pokémon fans would also swear that Pikachu has a black tip on his tail, but it has always been entirely yellow with a brown base.

Cinema has similar memory glitches, particularly with sci-fi and fantasy characters. Many Star Wars fans recall the protocol droid C-3PO as being entirely gold throughout the original trilogy. However, from A New Hope onward, his right leg from the knee down has always been silver. Another famous cinematic misquote involves the Wicked Witch of the West from The Wizard of Oz; people remember her shouting, “Fly, my pretties, fly!” when her actual line is simply, “Fly, fly, fly!”

Famous Movie Lines Everyone Misquotes

A classic example of the Mandela Effect in film comes from The Wizard of Oz. Many people recall the Wicked Witch of the West cackling, “Fly, my pretties, fly!” as she sends her winged monkeys to capture Dorothy. However, she never utters that phrase. Her real command is just, “Fly, fly, fly!” This misremembering shows how our minds can embellish iconic moments to make them more dramatic.

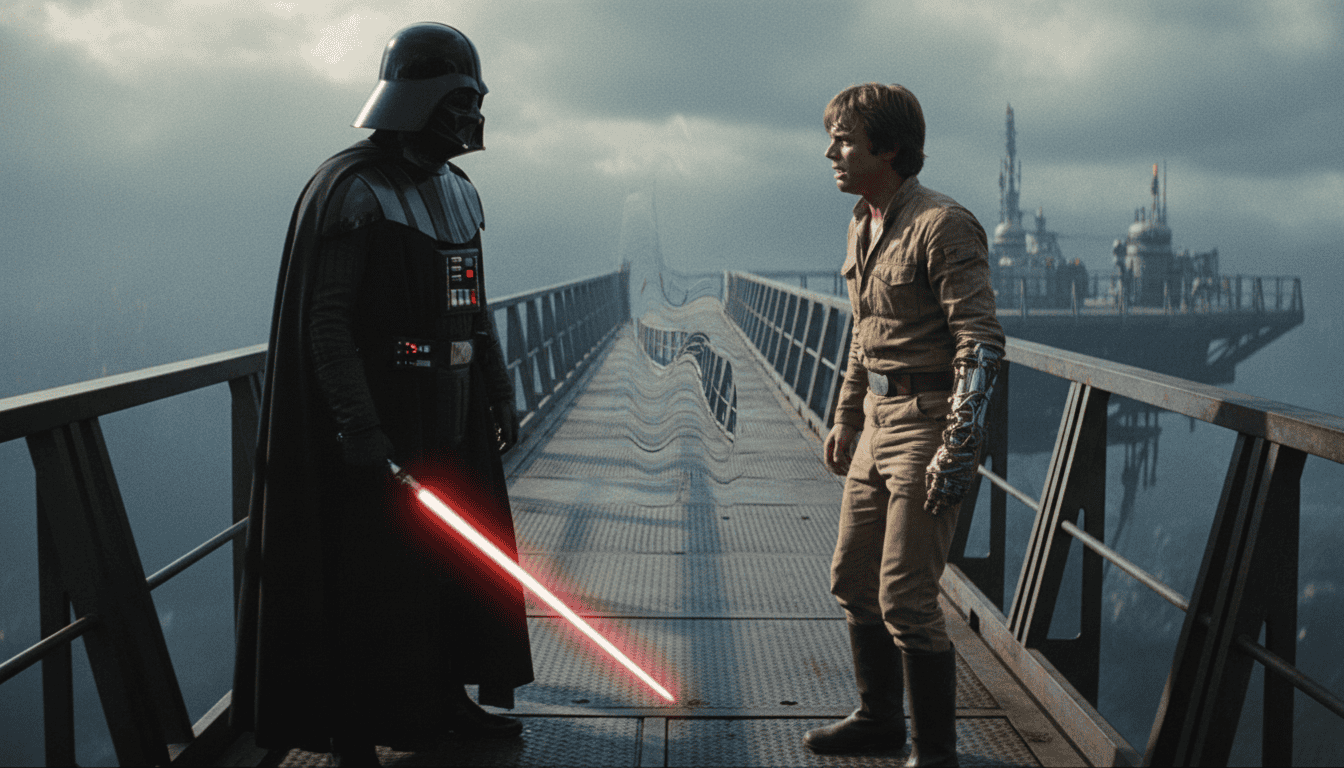

Science fiction provides another famous example. Darth Vader’s supposed confession, “Luke, I am your father,” is a widely parodied and remembered line. The actual line from The Empire Strikes Back is a direct response to Luke, with Vader saying, “No, I am your father.” The addition of “Luke” is a logical but incorrect embellishment that makes the quote more direct when repeated out of context, altering one of the most quoted lines in the saga.

Acclaimed thrillers also feature this phenomenon, such as The Silence of the Lambs. Hannibal Lecter’s greeting to Agent Starling is widely quoted as a menacing, “Hello, Clarice.” That line never appears in the film. When Clarice first approaches his cell, Lecter’s actual greeting is simply, “Good morning.” The misquoted version has become so pervasive that it is now the line most associated with the character, despite its absence from the film.

Brand Logos and Slogans We All Get Wrong

Iconic brand logos are often remembered with incorrect details. The red Target bulls-eye, for example, is frequently recalled as having three rings, but it only has two: a central red dot and a single outer red ring. This visual misremembering includes mascots like the Monopoly Man, who is widely pictured wearing a monocle despite never having one. The shoe brand Sketchers is also a source of confusion, as many remember it as “Skechers.” These subtle but widespread errors show how easily our minds can create a shared, false reality.

Brand slogans and names are also subject to collective misremembering. The classic M&M’s tagline is often recited as “Melts in your mouth, not in your hand.” The official slogan is actually the slightly longer, “The milk chocolate melts in your mouth, not in your hand.” The fast-food chain Chick-fil-A is frequently recalled and spelled as “Chic-fil-A.” This also applies to the spelling of the air freshener Febreze, which many people remember as “Febreeze.”

The Psychology Behind The Mandela Effect

The Mandela Effect is rooted in the fallibility of human memory and the creation of false memories. Our brains do not operate like video recorders; they reconstruct memories each time we recall them, a process influenced by suggestion and post-event information. This reconstruction can lead to confabulation, where our minds unconsciously fill memory gaps with fabricated details that feel real. Someone might vividly “remember” an event that never happened, like Nelson Mandela dying in prison, with the fabricated memory feeling as authentic as a genuine one.

Collective reinforcement transforms an individual false memory into a widespread phenomenon. When one person shares a misremembered detail online, such as the Monopoly Man wearing a monocle, it can trigger a similar misrecollection in others. This social validation creates a feedback loop where the more people who agree, the more credible the false memory becomes. The internet can act as an echo chamber, rapidly spreading and cementing these shared inaccuracies until a large group accepts them as fact.

Schema theory, which describes how our minds use mental shortcuts to organize information, is another psychological factor. We often fill in details based on pre-existing expectations. This explains why we might add a monocle to the Monopoly Man: it fits our schema of a wealthy tycoon. Source-monitoring errors also occur when we misattribute a memory’s origin, like confusing a parody of a movie line with the actual dialogue. This may be why so many people are convinced the Wicked Witch yells “Fly, my pretties, fly!” when the original line from The Wizard of Oz was just “fly, fly, fly.”

Conclusion

These shared misrememberings show how fragile our collective memory can be. From the Monopoly Man’s phantom monocle to the Wicked Witch’s misquoted command, the examples are both baffling and widespread. Each instance represents a glitch in our shared cultural consciousness: a detail that millions of people recall with certainty, yet which never existed. Forgetting a detail is common, but for a massive group to remember the exact same incorrect one is unusual.

The phenomenon makes us question the reliability of our minds and our shared history. Recalling a plaid skirt Britney Spears never wore or Mandela’s supposed death in prison are not isolated errors. These examples suggest our perception of the past is more malleable and subjective than we might admit. If so many of us can be wrong about trivial details, what more significant events or parts of our own histories might we be collectively misremembering?

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What exactly is the Mandela Effect?

The Mandela Effect is a phenomenon where a large group of people shares a specific, provably false memory of a past event or detail. This collective misremembering is so widespread that the correct version can feel jarringly wrong to those who experience it.

2. Why is it named after Nelson Mandela?

The term was created because many people incorrectly remembered South African leader Nelson Mandela dying in prison in the 1980s. He was actually released in 1990 and lived until 2013, but this widely shared false memory gave the phenomenon its name.

3. Is the Monopoly Man monocle a real Mandela Effect?

Yes, this is a classic example. Despite the widespread image of the Monopoly Man, Rich Uncle Pennybags, wearing a monocle, he has never been officially depicted with one in the game’s history.

4. Are there other common pop culture examples?

Yes. Many people are certain the Wicked Witch in The Wizard of Oz says, “Fly, my pretties, fly!” when her actual line is “fly, fly, fly.” Another example is Pikachu’s tail, which many remember having a black tip, but it has always been entirely yellow.

5. How can so many people remember the same wrong detail?

That question is the central mystery of the Mandela Effect. The phenomenon is defined by the fact that a distinct, incorrect memory is shared by a large, unrelated group of people. This collective nature is what makes the experience so unusual.

6. Are all Mandela Effects related to pop culture?

No. While pop culture provides many famous examples, the phenomenon gets its name from a real-world political event. The effect can apply to any shared memory, including historical events, brand logos, song lyrics, and movie lines.

7. Why do these false memories feel so vivid and real?

The vividness of the memory is a key characteristic of the Mandela Effect. For those who experience it, the false memory feels as distinct and real as any other. This is why discovering the truth can be surprising and confusing.