Remote Viewing: Inside the CIA’s Psychic Spy Program

Imagine a Cold War spy sitting not in a trench coat, but in a quiet, sterile room. Their mission: to infiltrate a secret enemy bunker using only the power of their mind. This scenario isn’t science fiction. It was the driving force behind real U.S. government programs that studied a phenomenon known as remote viewing, a person’s capacity to perceive details about a distant or unseen target without using any physical senses.

This was not a case of asking psychics for vague predictions. Researchers at the Stanford Research Institute in the 1970s developed strict, controlled protocols to test the ability and filter out guesswork. During a typical session, the ‘viewer’ is kept completely ‘blind’ to the target’s identity while recording raw sensory impressions like shapes, textures, and sounds. These impressions, a mix of mental ‘signal’ and ‘noise,’ were then compared against the actual target to determine their accuracy.

Key Takeaways

-

Remote viewing is a structured mental practice, not random psychic guessing, that uses strict, blind protocols to perceive information about a distant or unseen target.

-

The practice originated from top-secret U.S. government programs, like STARGATE, which were funded during the Cold War to explore its potential for espionage against adversaries like the Soviet Union.

-

A key principle of the protocol is to separate the raw sensory information, called the “signal,” from the viewer’s own analytical thoughts and imagination, known as “noise.”

-

Declassified documents revealed compelling successes, such as when viewer Pat Price accurately described the construction of a massive submarine inside a secret Soviet facility using only its geographic coordinates.

-

Despite such cases, mainstream science remains highly skeptical of remote viewing because its results are not consistently repeatable under controlled laboratory conditions.

-

After the government programs were declassified and shut down, the practice moved into the public sphere and is now taught and used by civilians, who often believe it’s a trainable skill.

Seeing the Unseen

Imagine describing a hidden object inside a locked box or a specific landmark in a city you’ve never visited. This is the core idea behind remote viewing, a structured mental practice for gathering information about a target that is out of reach of the physical senses. A person, known as a “viewer,” follows specific protocols to quiet their mind and record impressions like sights, sounds, textures, and even emotions related to the unknown target. The viewer has no conscious knowledge of what they are trying to perceive, which ensures their imagination or logical guesses do not interfere. The target itself can be anything: a person, a place, an object, or an event separated by distance or time.

Remote viewing is not daydreaming or random psychic guessing; it is a disciplined skill developed through practice. Formalized during the 1970s at the Stanford Research Institute, the practice uses strict protocols where both the viewer and their guide are kept “blind” to the target’s identity to prevent any clues from being passed¹⁵. During a session, the viewer sketches drawings and jots down sensory data that can feel fragmented and strange. The goal is to separate genuine information, called the “signal,” from the mind’s own chatter, known as “noise”¹¹. Only after the session concludes are these impressions compared against the actual target to judge their accuracy.

A Secret Born from War

The story of remote viewing begins not in a spiritual retreat, but in the tense, clandestine world of Cold War espionage. In the early 1970s, whispers of the Soviet Union’s success with “psychic spies” reached American intelligence agencies, creating a sense of urgency to keep pace. In response, the CIA and U.S. military secretly began funding a highly unusual research program at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) in California. Their objective was to determine if psychic abilities could be harnessed for intelligence gathering. This top-secret initiative, later known by code names like STARGATE, aimed to scientifically test and develop what researchers would call “remote viewing” (Source: declassified government documents).

At its core, the SRI program was built on a simple yet powerful idea: could a person “see” a location they had never visited, using only their mind? Researchers developed a strict protocol to test this, where a “viewer” would sit in a sealed room and attempt to describe a random, distant location being visited by an “outbounder” team. The viewer and the person monitoring them were kept “blind,” meaning they had no information about the target, to prevent any clues or guesswork. The initial results from early participants were so compelling that they secured two decades of government funding, pushing the boundaries of what was considered possible.

The Rules of Psychic Spying

A formal remote viewing session looks less like a mystical séance and more like a controlled scientific experiment. The viewer is kept completely unaware of the hidden target, ensuring no information is passed through conventional means. A “monitor” guides the viewer with neutral questions, and in the most rigorous sessions, this monitor is also blind to the target to prevent accidental cues¹⁵. This double-blind system, pioneered during experiments at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI), was designed to eliminate any possibility of cheating or subconscious guesswork.

During the session, the viewer does not try to name the target but instead describes raw sensory data, such as flashes of color, textures, sounds, or abstract feelings. The primary challenge is separating this pure information, or “signal,” from the viewer’s own thoughts and interpretations, a problem known as “mental noise” or “analytic overlay”. The original SRI protocols trained viewers to immediately identify and set aside their analytical mind’s attempts to label or guess what they are perceiving. This discipline allows them to stay focused on the faint, incoming signal without contaminating it with their own imagination.

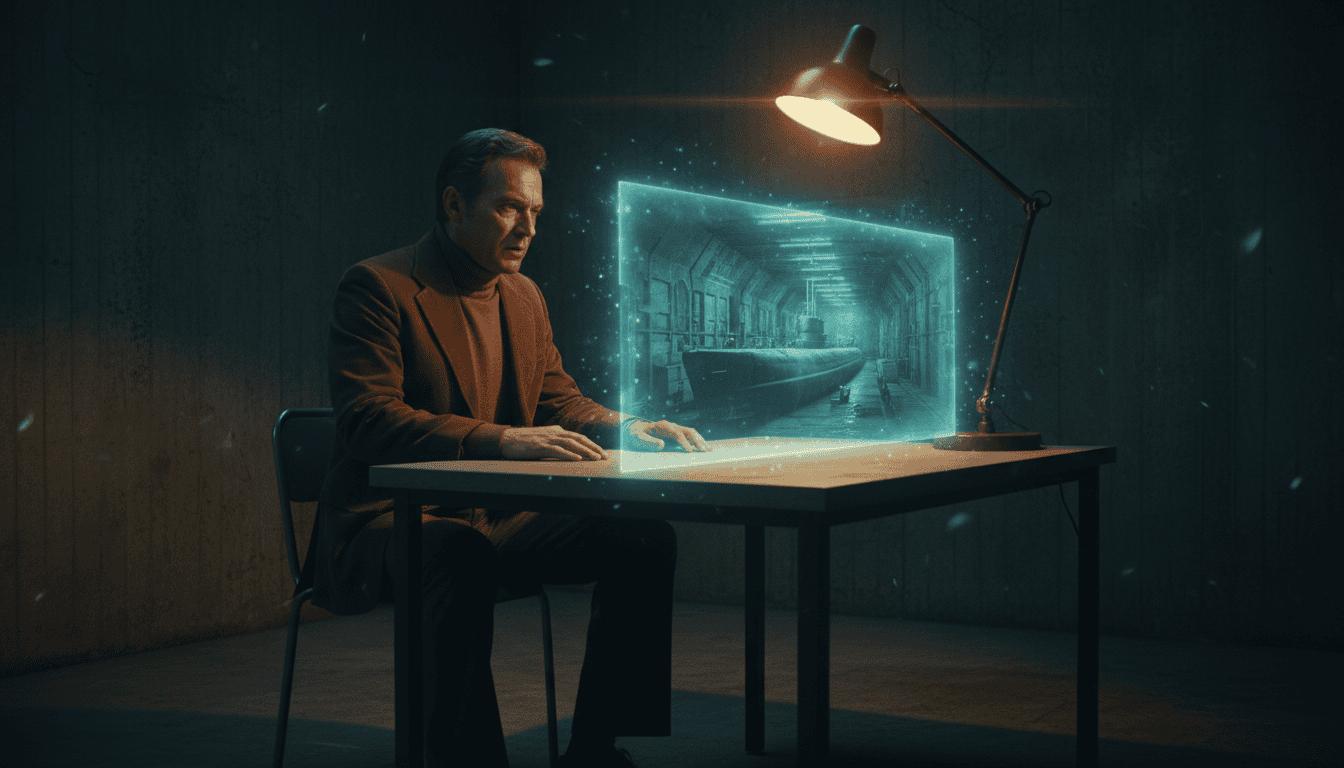

A Famous Glimpse Behind a Wall

In one of the most famous declassified cases, a viewer named Pat Price was tasked by the CIA to remotely view a secret Soviet facility in Semipalatinsk. The intelligence community was puzzled by satellite photos showing a large, unusual building under construction and needed to know what was happening inside. Price, a former police officer known for his remarkable psychic abilities, was given nothing more than the site’s geographic coordinates. His job was to mentally travel to this location and report what he “saw” behind its walls, thousands of miles away. This session would become a cornerstone example of remote viewing’s potential for espionage.

Price’s resulting sketches and descriptions were astonishingly detailed and incredibly accurate. He drew a massive gantry crane moving back and forth inside the building, describing its specific dimensions and function with uncanny precision. He also reported seeing large, cylindrical metal sections being welded together to form the hull of a massive submarine. At the time, American intelligence analysts were skeptical, as they believed the Soviets did not build submarines indoors. Declassified CIA documents later revealed that satellite imagery eventually confirmed all of Price’s major observations, validating a feat that seemed impossible.

Science, Skeptics, and Modern Viewers

Despite compelling results from government-funded programs, the mainstream scientific community remains largely unconvinced of remote viewing’s existence. The primary hurdle for its acceptance is the issue of repeatability, a cornerstone of scientific validation. Skeptics argue that successful experiments are often statistical flukes or can be explained by subtle cues and flawed protocols rather than genuine psychic ability. For every startling “hit,” they argue, there are countless misses and ambiguous drawings that receive far less attention. This lack of consistent, irrefutable proof under tightly controlled conditions keeps remote viewing on the fringes of accepted science.

When the U.S. government officially shuttered its psychic spy programs, the practice of remote viewing did not disappear but instead moved into the public sphere. Former program members, like the famous viewer Joseph McMoneagle, and a new generation of enthusiasts carried it on. Today, numerous private organizations and individuals train and practice remote viewing for various purposes, from personal spiritual growth to attempting to solve cold cases or even for corporate espionage. These modern viewers often operate outside the strict, blind protocols of the original research, forming a dedicated subculture that shares its findings online, convinced of the reality of a skill that science has yet to embrace.

This divide creates a fascinating dynamic where scientific skepticism coexists with passionate personal testimony. While a scientist demands data that can be replicated in any lab, a private viewer might point to a single, unexplainable success as all the proof they need. Proponents suggest that the consciousness-based nature of remote viewing may not be compatible with the rigid framework of conventional science, claiming the “signal” is easily disrupted by doubt. This leaves the curious observer to wonder whether the truth of remote viewing lies in the data, the experience, or somewhere in the mysterious space between.

Conclusion

Remote viewing’s journey from classified government files to public consciousness is a remarkable story. What began as a top-secret experiment during the Cold War, funded by agencies like the CIA, sought to explore a seemingly impossible human skill for intelligence gathering. When the Stargate Project was declassified in the 1990s, the once-hidden protocols and documented sessions became the stuff of legend and intense debate. Today, it has evolved into a practice explored by civilians, artists, and spiritual seekers, far from its original military-intelligence roots.

The story of remote viewing leaves us at a fascinating crossroads of belief and skepticism. Could it be a latent, untapped sense that all humans possess, a natural ability to perceive information beyond the conventional five senses? Or are the seemingly accurate results merely the product of statistical noise, confirmation bias, and the brain’s incredible ability to find patterns where none exist? Perhaps the truth lies somewhere in the middle, a complex interplay between psychic potential and psychological suggestion. After exploring the evidence, the history, and the firsthand accounts, what do you believe remote viewing truly is?

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is remote viewing, in simple terms?

Remote viewing is a structured mental practice for describing a target that is distant or hidden from the physical senses. A person, called a “viewer,” uses specific protocols to gather impressions about a person, place, or object they have no conscious knowledge of.

2. Is remote viewing the same as being psychic?

While related, remote viewing is distinct from general psychic ability because it is a standardized, repeatable skill developed through strict protocols. It was designed in a research setting to separate verifiable sensory data from imagination, unlike spontaneous or unstructured psychic visions.

3. How does a remote viewing session actually work?

In a typical session, the viewer is kept completely “blind” to the target’s identity to prevent guessing. They follow a formal process to quiet their mind and record raw sensory data, such as textures, colors, sounds, and shapes, before their analytical mind can form conclusions.

4. Where did this practice come from?

Remote viewing was developed and formalized during the 1970s at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI). This work was part of U.S. government-funded intelligence programs that explored its potential use for espionage during the Cold War.

5. Can anyone learn to become a remote viewer?

Many practitioners believe remote viewing is a trainable skill, not a rare gift. Just like learning a musical instrument, it requires discipline and consistent practice following established protocols to improve their ability to perceive information.

6. How do you know the information is accurate and not just a guess?

The strict “blind” conditions of the protocol are the first line of defense against guesswork. Afterward, the viewer’s recorded impressions are formally compared against the actual target by an analyst to determine the level of accuracy and correlation.

7. What kinds of things can be a target for remote viewing?

A target can be almost anything, separated by distance or time. Viewers have been tasked with describing everything from a hidden object in a locked box to a specific landmark in a foreign city or even a significant event.